Making sense of differing descriptions of C-PTSD.

- Complex PTSD refers to different things for different people.

- Among clinicians, C-PTSD is often used to refer to someone with both Axis I and Axis II disorders.

- For trauma sufferers, C-PTSD validates their experience of multiple layers of trauma.

- The two perspectives can be unified by adopting a larger, more compassionate view of trauma’s impact.

Complex PTSD, or C-PTSD, refers to different things for different people.

Among clinicians, C-PTSD is often used as a polite way to refer to someone with both Axis I and Axis II disorders—that is, someone who not only has an anxiety disorder but whose personality also has diagnostic significance. Among some clinicians, C-PTSD is used interchangeably with borderline personality disorder; they are expressing that effective treatment often involves addressing difficulties with emotional dysregulation, self-perception, and maladaptive behaviors in close relationships.

C-PTSD is used in quite a different way among those who suffer from trauma—as a better term to describe the challenges they face relative to the conventional understanding of PTSD. For many of my patients, C-PTSD is a term that validates their experience of multiple layers of trauma. What they’re expressing is that they’ve had early-life trauma in addition to subsequent trauma exposure in adulthood.

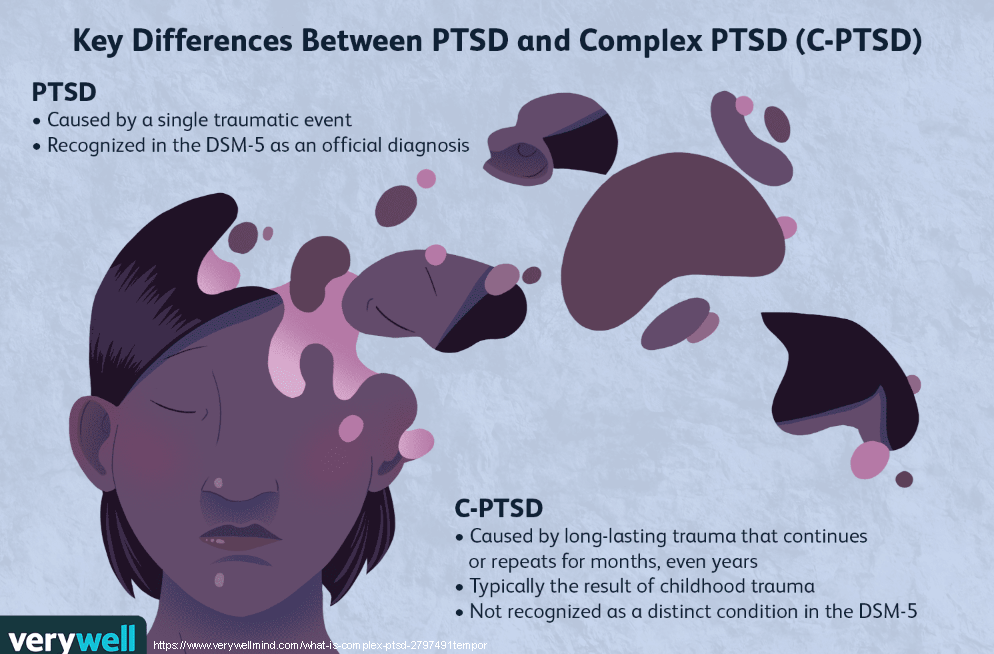

My patients often contrast this set of experiences with the conventional understanding of PTSD, which is diagnosed after someone is exposed to an event that causes a feeling of helplessness or horror. In such classical descriptions, there is often a major focal trauma that changes the life course of an individual.

For example, suppose that an individual has had a catastrophic car crash and develops PTSD as a result. It’s important to note that the very term “PTSD” has actually been evolving into “post-traumatic stress injury.” Other classical focal traumas might be an assault or a trauma sustained during combat operations. In such cases, the clinical treatment plan often involves identifying the central trauma, what psychologists call an “index” trauma, and doing work to process and resolve that trauma.

But with complex PTSD, there is often no clear index trauma. Individuals with complex PTSD often have a high ACEs score. ACE refers to adverse childhood experiences and is a measure of adverse childhood events such as physical or emotional abuse, neglect, caregiver separation or divorce, exposure to family member addiction, or witnessing violence.

Identifying the presence of childhood trauma is often critical to patient outcomes. Research is now reshaping the understanding of the landscape of trauma. For example, research is confirming that for many veterans, the trauma of warfare is not the trauma that causes the greatest damage. Studies show that military service members often enter the military with significant childhood trauma. It is often the trauma from their childhood that was never addressed before they entered the military that causes the greatest negative impact.

In addition, cultural influencers like Oprah Winfrey and Dr. Bruce Perry are changing the way that society views trauma and trauma sufferers, refocusing through a more compassionate lens—not a “What’s wrong with you?” but rather a “What happened to you?” approach.

It’s interesting that C-PTSD is often used in different ways by clinicians and trauma sufferers. Could these two very different perspectives potentially merge? I believe they can. The alignment would come from shifting understanding:

When people suffer continual trauma in early childhood, their personalities form in the crucible of the trauma exposures. Trauma shapes and changes them in ways that are both biological and psychological. Attachment research offers a valuable perspective on how default trust (or lack thereof) is developed in early-childhood relationship contexts. From my perspective as a trauma psychologist, it should not be surprising, or an exception to the rule, that people who have suffered early childhood trauma may develop personality features that are shaped by that trauma.

This does not mean that everybody with early trauma has borderline personality features or meets the criteria for such a diagnosis. It’s just the inverse. Those with borderline personality features or other relationship-altering personality features may be explained in large part because of early childhood trauma experiences.

This is the compassionate frame we can adopt to destigmatize mental wellness and help those who suffer from trauma begin to heal.

References

https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/complex_ptsd.asp

Blosnich, J. R., Dichter, M. E., Cerulli, C., Batten, S. V., & Bossarte, R. M. (2014). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA psychiatry, 71(9), 1041–1048.

Kang, H. K., Bullman, T. A., Smolenski, D. J., Skopp, N. A., Gahm, G. A., & Reger, M. A. (2015). Suicide risk among 1.3 million veterans who were on active duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Annals of Epidemiology, Volume 25(2), 96-100.