- Research has tied adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to adult mental health.

- These studies were not conclusive since correlation does not equal causation.

- A new study from Sweden showed that genes, ACEs, and more general environmental variables likely play a role.

Early in my career, I interned for a year at a state psychiatric hospital. The men and women I worked with were dealing with serious mental illness, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, as well as substance use disorders.

As I talked with many of these individuals, I heard horrifying stories about their childhoods; abuse, family violence, and other adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were rampant. It wasn’t hard to connect the dots between their early experiences and their current mental health struggles.

Separating Genetic and Environmental Effects

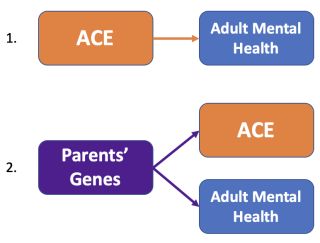

Many research studies have confirmed that a rough childhood is linked to greater risk for mental illness in adulthood. However, it is hard to know whether the ACEs themselves are the cause of the psychiatric issues later in life. It’s possible that a third variable, such as shared genes, is to blame for both the adversity and the subsequent mental health challenges.

Source: Seth Gillihan

After all, commonly measured ACEs such as parental mental illness and substance use are themselves significantly tied to genetic factors. For this reason, what appears to be an effect of ACEs on mental health could in fact be caused by genetic factors that impact both the adverse experience (through the parent’s genetic risk) and the child’s mental health outcomes (see the figure).

In a similar way, more general aspects of the environment could be driving the ACE-mental health association. ACEs typically don’t happen in a vacuum but are connected to longer-standing factors such as neighborhood crime rates or being raised by a highly critical parent.

It could be the case that these chronic forms of low-grade stress are more potent than the less frequent but more intense events that are usually measured in studies of ACEs.

Powerful New Study From Sweden

Researchers recently took advantage of the incredible health records in Sweden to explore the effects of ACEs on adult mental health (Daníelsdóttir et al., 2024). They used a nationwide sample of more than 25,000 twins, which allowed them to separate the effects of shared genes, shared environments, and individual-specific ACEs such as physical neglect, emotional or sexual abuse, or hate crimes.

Adult mental health outcomes were measured by whether the participant had received after age 19 an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, or stress-related disorder. The study also measured depression symptoms during the past week as an indicator of current mental health.

Initial analyses showed that ACEs had a big impact on adult mental health. The effects were “dose-dependent,” meaning that each additional ACE raised the risk for mental illness. According to the study, “Every additional ACE was associated with 52% greater odds of any psychiatric disorder,” which held for both males and females.

Using Twin Pairs to Disentangle Cause and Correlation

The twin aspect of the study was key in separating the effects of ACEs from genetic and general environmental effects. Researchers zeroed in on twin pairs who were “discordant” on exposure to ACEs—that is, pairs in which one twin was exposed to a certain type of adverse experience and the other was not. They then re-analyzed the effects of ACEs on the risk for adult psychiatric diagnosis.

If ACEs had less of an effect on adult mental health outcomes among discordant twin pairs, this finding would suggest that it was not the ACE per se that was driving the effect. For example, imagine that one twin experienced physical neglect and the other did not, but both wound up with depression in adulthood. This result would indicate that it was not the neglect itself that caused the subsequent depression. Alternative explanations would include the twins’ shared genes (100 percent in identical twins and 50 percent on average in non-identical twins) and shared aspects of their childhood environment that aren’t captured by measures of ACEs (e.g., growing up in a high-stress neighborhood).

On the other hand, imagine that the effect of each additional ACE on mental health outcomes in these discordant twin pairs turned out to be about 52 percent, as in the initial analysis of all participants. This result would suggest that ACEs are, in fact, the cause of adult psychiatric outcomes since their effect is just as potent among sets of twins in which only one experienced the ACE.

Shared Genes and Environments Plus Childhood Adversity

Perhaps not surprisingly, the discordant twin pair analyses showed that ACEs still contributed significantly to adult mental health diagnoses. However, the effects were not as strong. In identical twins, the effect of each ACE raised the odds of having a psychiatric condition by 20 percent; for non-identical twins, the odds increased by 29 percent. Therefore, the effects of ACEs were approximately 40 to 60 percent lower than what they were among the full group of participants (52 percent).

These findings reveal that more general environmental conditions such as living in an impoverished school district played a role in adult mental health outcomes. Genetic predispositions might also drive part of the apparent effect of ACEs on psychiatric disorders after age 19.

The study authors note that their findings can’t determine the relative contributions of genetics and general aspects of the childhood environment. Participants also reported their ACEs retrospectively as adults, so it is possible that “current mental health status influenced the reporting of ACEs.” More research is needed to address these limitations.

For now, the takeaway is clear: A difficult childhood environment and genetic factors can contribute to mental illness in adulthood; when kids experience serious adverse experiences on top of these long-term risk factors, the likelihood of an adult psychiatric condition is even greater.

References

Daníelsdóttir, H. B., Aspelund, T., Shen, Q., Halldorsdottir, T., Jakobsdóttir, J., Song, H., … & Valdimarsdóttir, U. A. (2024). Adverse childhood experiences and adult mental health outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry.