Grant Hilary Brenner MD, DFAPA

Identifying suicide risk can improve prevention of this rising cause of death.

KEY POINTS

- Suicide rates are a rising cause of death.

- Suicide prevention efforts have increased, notably with the advent of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

- Suicide is hard to predict, and risk-prevention models need refinement to be more effective.

- Identifying unique classes of risk factors opens up opportunities for more effective prevention measures.

Suicide is an increasingly common cause of death. Suicide rates in the United States have increased by more than 35% in the past two decades. According to the National Institute of Mental Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in 2021, accounting for more than 48,000 deaths—twice the number of homicides. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for 10- to 14-year-olds and 25- to 34-year-olds. It’s the t hird leading cause of death among those 15 to 24.

Prediction is key for prevention. The proposed disorder suicide crisis syndrome, in which high emotional pain and feeling trapped (“entrapment”) precipitate increased risk 2, provides a model for conceptualizing suicide as a psychiatric emergency analogous to a heart attack. Artificial intelligence could be used to help researchers identify patterns of brain activity3 distinguishing lethal from non-lethal intent.

Interviews with near-lethal suicide attempt survivors4 has identified seven themes: Developmental conflicts and crises; character traits and vulnerabilities; interpersonal and object relations paradigms; thinking and affect; fantasies of death; the paradoxical nature of the immediate moment of the suicide attempt; and reactions to survival. Research suggests that survivors of suicide may experience PTSD as a result5, increasing future risk.

Refining How We Understand Suicide Risk

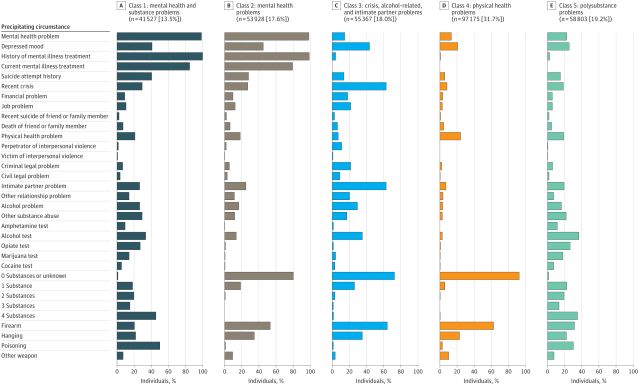

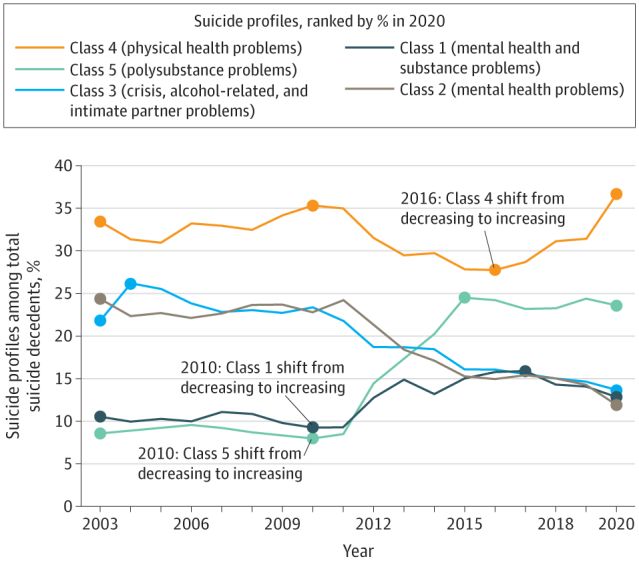

Research published in JAMA Psychiatry (2024) identified five different patterns of suicide. J. John Mann, M.D.6 and colleagues analyzed data on 306,800 people whose death was recorded in the 2003-2020 CDC National Violent Death Reporting Systems Restricted Access database. The team examined a range of factors and, using latent class analysis (LCA), identified five distinct profiles.

- Class 1–Mental health and substance problems (13.5 percent). Mental illness and substance use occurred together. Depression, prior suicide attempts, and being currently in mental health treatment were typical. Poisoning was more common, including overdose with medications and substances. More than 45 percent in this group died with four or more substances in their system. Suicide notes were more common, and rates of psychiatric medication were higher.

- Class 2–Mental health problems (17.6 percent). Those in this group had high rates of mental health problems with significantly lower substance use, More than 80 percent had no substances detected. Hanging was more common.

- Class 3–Crisis, alcohol-related, intimate partner problems (18 percent). This group was characterized by a more chaotic pattern of crisis, alcohol-use, and relationship difficulties. Firearms were often used.

- Class 4–Physical health problems (31.7 percent). The largest class was distinguished by having the most physical health problems. They were least likely to have sought mental health treatment or shared their problems. They had the lowest identified mental health problems, positive drug and alcohol tests, and fewest prior suicide attempts. Suicide notes were least common, as was non-disclosure of suicidal intent. Suicide increased sharply in 2016. Firearms were more common, and this group was predominantly male. Class 4 had higher proportions of older adults, Asian Americans, and veterans, and those in it were more likely to die on the first attempt due to high firearm use.

- Class 5–Polysubstance problems (19.2 percent). This class had the highest substance and alcohol use problems in the absence of mental illness. Firearms were a main cause of death. This group was smaller, declining until 2010, when it steeply increased until leveling off in 2015.

Latent Class Detail

Source: Xiao et al. 2024 / JAMA Psychiatry Open Access

Integrating Findings and Recommendations for Suicide Prevention and Intervention

Overall, of the 306,800 suicide deaths, 78.1 percent involved men and 21.9 percent women. Eight-two percent were White, 6.5 percent Black, 2.3 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, 6.3 percent Hispanic, and 1.3 percent Native American. Veterans comprised 16.9 percent. The majority, nearly 80 percent, had resided in urban settings. Generally, factors such as economic and divorce or separation-related stress, common among women in Class 1, contributed to increased risk.

Suicide Class Trends

Source: Xiao et al., 2024 / JAMA Psychiatry Open Source

Suggestions based on the findings include:

- Generally, integrating mental health services into general health settings, especially for Class 4 (see below).

- Class 1 (Mental health and substance problems). Integrating mental health and substance-related care, monitoring for medication non-adherence, and “community-based rehabilitation to foster recovery and social integration.”

- Class 2 (Mental health problems). Intensifying mental healthcare with targeted therapy and medication especially for those with depression and borderline personality disorder.

- Class 3 (Crisis, alcohol-related and intimate partner problems). Providing crisis interventions, family and couples work, and alcohol use disorder treatment.

- Class 4 (Physical health problems). Bolstering mental health and suicide screening, especially in nonpsychiatric settings, such as primary care and emergency rooms, given the lower relative frequency of mental health visits in the month leading up to suicide. Focusing on addressing underlying risk factors, such as tending not to seek help or share struggles, putatively because of stoicism stemming from such factors as gender and cultural influences.

- Class 5 (Polysubstance problems). Increasing substance use disorder treatment, including using harm reduction and peer support models, as well as identifying and treating unrecognized mental health problems.

- Critically, measures to reduce the risk from high lethality methods. This is especially important for firearms7.

In addition,the authors highlight the importance of inclusivity in addressing the suicide epidemic, given the diversity of culture, educational background, race and ethnicity, age and related factors.

The research represents a significant step toward a more refined understanding of suicide risk. A granular understanding of different profiles of and paths toward suicide may to lead to fewer suicide deaths, allow catching people earlier. as risk ramps up, and modifying the underlying factors.

Raising public awareness of suicide is essential for reducing stigma and cultivating an atmosphere in which recognition of and communication about suicide contributes to prevention and appropriate care. Best practices involve assessing suicide probability based on risk and protective factors, and using a variety of prevention approaches from safety planning to rapid-acting biological treatments.

If you or a loved one are concerned about suicide or self-harm, please seek appropriate evaluation immediately. The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is available for calls, text and chat. 911 and the Emergency Department can be used for emergencies.

References

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline & Vibrant Emotional Health 988

1. CDC Leading Causes of Death & NIMH Suicide

2. The suicide crisis syndrome: A network analysis

3. Can Artificial Intelligence Predict Suicide?

4. 7 Themes Reported by Near-Lethal Suicide Attempt Survivors

5. Can You Get PTSD from Attempted Suicide?

6. Director of the NIMH Conte Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders, and Past President of the International Academy of Suicide Research

Xiao Y, Bi K, Yip PS, et al. Decoding Suicide Decedent Profiles and Signs of Suicidal Intent Using Latent Class Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(6):595–605. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0171

An ExperiMentations Blog Post (“Our Blog Post”) is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Grant H. Brenner. All rights reserved.