The country faces a speedballing, fentanyl and meth overdose crisis.

KEY POINTS

- Methamphetamine abuse is growing in the United States.

- Overdoses that include methamphetamine are on the rise.

- Methamphetamine plus Fentanyl in pills, smoke, or i.v. use cause the majority of deaths.

Methamphetamine is a highly addictive psychostimulant and one of the most widely abused drugs worldwide. Production and distribution of methamphetamine have increased significantly, leading to greater availability and lower prices. This is partly due to establishment of large-scale production operations in Mexico, a major supplier to “meth” users nationwide. In 2024, approximately 2.5 million people in the United States reported using methamphetamine in the past 12 months.

Methamphetamine poses severe health and social risks, including overdose deaths, cardiovascular damage, psychotic behavior, and increased rates of infectious diseases from injecting the drug with shared needles. Meth is eaten, sniffed-snorted, smoked, or injected. Many users combine methamphetamine with fentanyl, known as “speedballing,” a particularly lethal combination. Counterfeit drugs sold as methamphetamine are often adulterated with fentanyl, increasing fatal overdose risks.

Source: Public domain

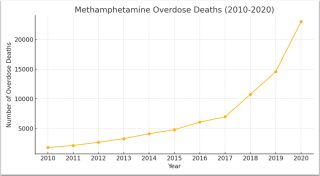

Deaths involving methamphetamine have surged dramatically since the mid-2010s, based on federal data. There is no antidote to reverse meth’s toxicity as opioid overdoses are reversible with naloxone and nalmefene. As depicted in the table at left, methamphetamine overdose deaths have dramatically increased. A significant driver of this increase is mixing methamphetamine with fentanyl.

Meth Abusers

Based on data from the Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) for 2015-2018, the highest rates among adult users were among white or Hispanic males. In considering age, the highest rates by age occurred among those 26-34 years old, followed by those 18-25. Annual household income was also a factor: The meth abuse rate was highest among people with an annual income of less than $20,000. It’s also important to note abuse was low among people with no past-year mental illness (3.4 people per 1,000 adults) and highest among people with a past-year serious mental illness (37.6 per 1,000 adults.)

Symptoms of Methamphetamine Abuse

Patients under the influence of methamphetamine may exhibit symptoms mimicking psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. Often intoxication with meth includes euphoria, hyperactivity, anxiety, and pressured and disturbed speech. Patients also may present with agitation, irritability, or violent aggressiveness. Methamphetamine users may experience a pre-psychotic state with delusional moods followed by psychosis with hallucinations and delusions. Patients often become suspicious or paranoid of friends and family members. They may act on these false beliefs, harming others.

Usually, acute symptoms last 4 to 7 days after drug cessation. Meth users experience impairments in learning and memory functions thought to be secondary to meth-induced abnormalities in the hippocampus of the brain. Long-lasting meth psychosis often requires locked psychiatric hospitalization. Methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) is characterized by compulsive and continued use despite adverse consequences.

Neurologic/Brain Signs of Methamphetamine Abuse

Neurologic signs of methamphetamine use include hemorrhagic strokes in young people with no previous evidence of neurologic impairments.

Brain imaging performed on methamphetamine users shows damage similar to observed in Parkinson’s Disease patients, as well as changes similar to those produced by head trauma or injury. Studies have documented similarities between methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and traumatic brain injury. Chronic users show signs of cognitive decline affecting a broad range of neuropsychological functions. Specifically, episodic memory, executive functions, complex information processing speed, and psychomotor functions have been reported negatively impacted.

Source: Morehouse University School of Medicine

Meth Overdoses

Methamphetamine overdose is common and can be fatal. Hyperthermia (a dangerously high body temperature) is an acute effect of methamphetamine use that may cause muscular and cardiovascular dysfunction, kidney failure, heat stroke, and other heat-induced syndromes. There are no medications for methamphetamine-induced thermal dysregulation, and treatment is focused on reducing patients’ body temperature, packing them in ice or using cooling fans or cold-water baths. Patients should be given naloxone or nalmefene regardless of medical history because of the likelihood of methamphetamine adulteration with fentanyl. No current antidote exists, nor is any treatment approved by the FDA for overdose. Patients in the ER for methamphetamine should be screened for opioid use and other substance use disorders (SUDs) and given harm reduction supplies like naloxone. If indicated, treatment with medications for opioid use disorder should be recommended.

Emerging Treatments for Methamphetamine Use Disorder

There is no medication approved by the FDA for treatment of methamphetamine use disorder (MUD). In one study of adults with MUD, of those treated with extended-release injectable naltrexone plus oral extended-release bupropion, short-term study success or harm reduction outcomes were low but higher than among participants who received placebo.

Other ideas involve treatment with nutraceuticals and other alternatives. According to neuroscientist Ken Blum, Ph.D., “There may be several possible ways to repair the brain systems targeted by methamphetamine aim such as exercise, diet, biofeedback, meditation, and neuromodulation. The nutraceutical approach I’ve developed may activate dopaminergic neuropathways as measured by functional magnetic imaging and has been shown to recruit new dopaminergic neurons.”

Most exciting is the emerging development of vaccines to prevent methamphetamine intoxication or overdose. No vaccines are yet FDA-approved. However, widespread use of stronger, more lethal substances like fentanyl among methamphetamine users has accelerated interest in vaccine therapies.

Source: Baylor College of Medicine

Tom Kosten, MD, professor and Co-Director of the Institute for Clinical & Translational Research at the Baylor College of Medicine, and an SUD vaccine development pioneer. explains, “Vaccines have the greatest promise for fentanyl and its derivatives as well as for new compounds like nitzazine. Fentanyl vaccines can help with methamphetamine overdoses because lethal OD usually involves MA [methamphetamine] + fentanyl.”

Summary

Methamphetamine use, abuse, or overdose can be deadly. Doctors treat it with naloxone or nalmefene because many ODs are methamphetamine plus fentanyl. Meth psychosis is very difficult to treat. Long-lasting behavioral, neurological, cognitive, movement and other consequences of meth are real, yet without specific treatment. To date, methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) treatments are weak interventions and underdeveloped. We need to do better.

References

Kosten TR. Vaccines as Immunotherapies for Substance Use Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2024 May 1;181(5):362-371. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20230828. PMID: 38706331.

Jammoul M, Jammoul D, Wang KK, Kobeissy F, Depalma RG. Traumatic Brain Injury and Opioids: Twin Plagues of the Twenty-First Century. Biol Psychiatry. 2024 Jan 1;95(1):6-14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.05.013. Epub 2023 May 20. PMID: 37217015.

Trivedi MH, et al. Bupropion and Naltrexone in Methamphetamine Use Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jan 14;384(2):140-153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020214. PMID: 33497547; PMCID: PMC8111570.

Febo M, et al. Enhanced functional connectivity and volume between cognitive and reward centers of naïve rodent brain produced by pro-dopaminergic agent KB220Z. PLoS One. 2017 Apr 26;12(4):e0174774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174774. PMID: 28445527; PMCID: PMC5405923.