No two people have the exact same depression. What explains these differences?

Key points

- Depression affects 280 million people, but it looks different in everyone.

- How we define depression plays a huge role.

- Age, sex, and cultural differences also play a role.

Globally, over 280 million people have depression. But if you were to ask a random sample of 1,000 people to describe their depression, you would have a low chance of finding two people who have the exact same experience.

Why is that?

Defining Depression

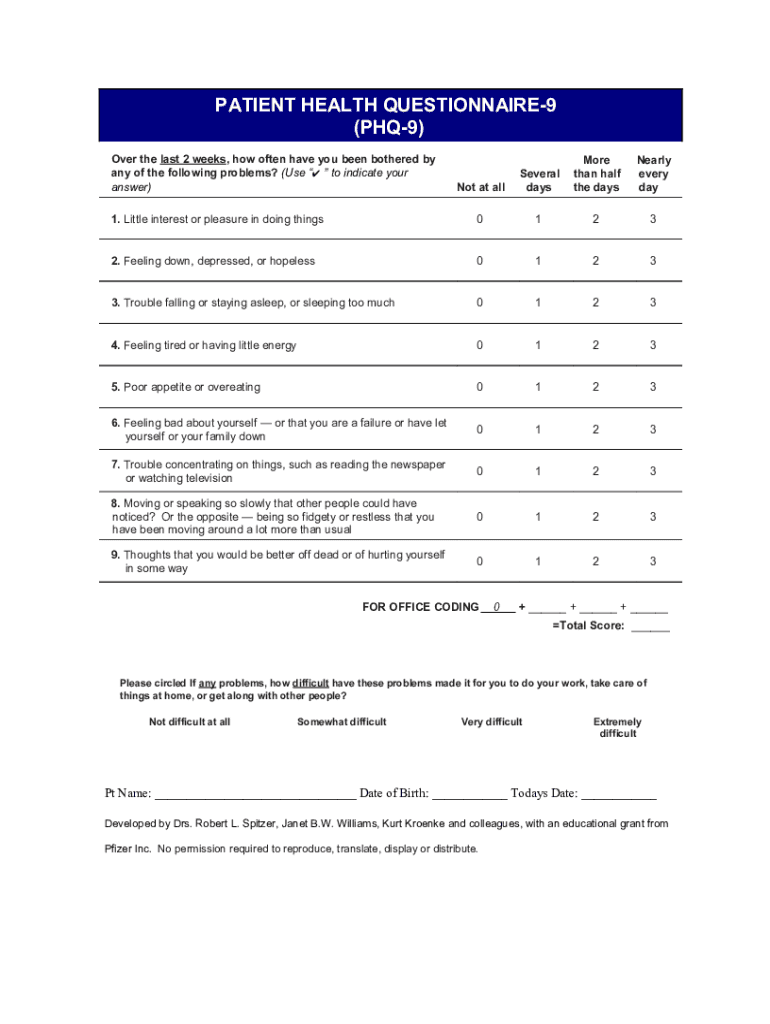

We first need to define depression to understand why it looks different in everyone. Depression, or a Major Depressive Episode, is a mental health diagnosis that is characterized by nine symptoms: (1) depressed mood; (2) “anhedonia,” or markedly diminished interest or pleasure; (3) increase or decrease in either weight or appetite; (4) insomnia or hypersomnia; (5) psychomotor agitation or retardation; (6) fatigue or loss of energy; (7) feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt; (8) diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness; and (9) recurrent thoughts of death or recurrent suicidal ideation (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

A diagnosis requires that someone has at least five of these symptoms, one of which must be either depressed mood or anhedonia. These symptoms need to be persistent for at least two weeks and cause significant distress or impairment. Additionally, these symptoms should not be better explained by another factor, like a new medication.

So, if we have these defined criteria, why does depression vary so much from person to person?

5 Reasons Why Depression Looks Different in Everyone

1. The criteria are not one-size-fits-all. The definition of depression, itself, invites differences from person to person. Research shows that it is rare that any two individuals will have the exact same combination of symptoms—as you can see in the criteria above, depression is defined by a combination of five out of nine symptoms. One study, led by Eiko Fried and Randolph Nesse (2015), analyzed over 3,000 patients and investigated how often patients share the same symptom experience. Their study revealed that how we define depression can result in over 1,030 unique symptom profiles! The most common symptom profile was only endorsed by 1.8% of the sample. Put simply, there are many, many ways to meet the criteria for depression.

Source: Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams (2001) / No Permission Needed

2. Depression is defined by subjective experiences. Depression is a diagnosis that is rooted in subjective experiences like mood, emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. The word “subjective” does not mean someone’s experience is not real—if someone feels sad, then they feel sad. But as a psychologist, I cannot give someone a blood test to assess if they are “happy” or “sad,” nor can I use a brain scan to assess for suicidal thoughts. Even for the physical symptoms, like loss of energy, there is no reliable objective test to determine the severity of someone’s fatigue. To diagnose depression, clinicians must conduct interviews with patients to assess how they feel. And, as we all know, one person’s “sad” looks a lot different than another person’s “sad.”

3. Depression presents differently across age groups. How depression looks can vary across children, teenagers, and adults. Research shows that specific symptoms may show up more frequently in certain age groups. In one study by Rice and colleagues (2019), they analyzed how frequently depression symptoms were endorsed by adolescents and adults. Their study found that “vegetative symptoms”—like appetite and weight change, loss of energy, and insomnia—were more commonly seen in adolescent depression than adult depression. Meanwhile, adult depression was more likely to include symptoms of anhedonia and concentration problems. These findings can help people become more sensitive to noticing signs of depression based on age.

4. Sex differences exist between men and women. Large global studies have consistently found that women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression than men. Among adults in the United States, 10.3% of women—compared to 6.2% of men—met criteria for depression in 2021 (NIMH, 2023). The reasons for these sex differences are complex, driven by an interplay of social, psychological, and biological factors (Eid et al., 2019). It is also possible that how we define depression makes it easier for women to meet the criteria, and men may present with depression differently (Martin et al., 2013). In support of this idea, Cavanagh and colleagues (2017) conducted a large review of studies and found that men with depression were more likely to have difficulties with alcohol use, drug use, and risk-taking/poor impulse control behaviors. Meanwhile, women had a higher frequency and severity of traditional depression criteria, like depressed mood, appetite/weight changes, and sleep difficulties. Recognizing these differences can help both men and women get help for depression.

5. Cultural differences are real, but more research is needed to understand these differences. Cross-cultural research shows that the expression of positive and negative emotions can vary across countries and cultures. This is important to note because depression—a diagnosis characterized by mood and emotions—is mostly defined from a Westernized perspective. The criteria were not developed and tested in other countries, and thus our estimates of depression around the world may be somewhat biased. For example, a multinational analysis of 116 countries found that countries meaningfully varied in their expression and valuing of emotions (Tay et al., 2011). While the range of emotions if felt universally across cultures, some cultures are more likely to express joy than others, and the same rule of thumb applies for negative emotions (Cordaro et al., 2018). However, a new study by Panaite and Cohen (2024) found some consistency across countries in terms of how emotions were reported among adults with depression, compared to adults without depression. Their study highlighted the need for more cross-cultural research to understand the complexities of how depression is experienced across the world.

The Takeaway

There is no “one” look to depression. Depression does not have one mascot that represents everyone’s experience. However, by understanding why depression varies from person to person, we are better positioned to provide one-fits-one care and support from person to person.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Cordaro, D. T., Sun, R., Keltner, D., Kamble, S., Huddar, N., & McNeil, G. (2018). Universals and cultural variations in 22 emotional expressions across five cultures. Emotion, 18(1), 75.

Eid, R. S., Gobinath, A. R., & Galea, L. A. (2019). Sex differences in depression: Insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Progress in Neurobiology, 176, 86-102.

Fried, E. I., & Nesse, R. M. (2015). Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR* D study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 96-102.

Haroz, E. E., Ritchey, M., Bass, J. K., Kohrt, B. A., Augustinavicius, J., Michalopoulos, L., … & Bolton, P. (2017). How is depression experienced around the world? A systematic review of qualitative literature. Social Science & Medicine, 183, 151-162.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2023). Major Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression

Panaite, V., & Cohen, N. (2023). Does Major Depression Differentially Affect Daily Affect in Adults From Six Middle-Income Countries: China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russian Federation, and South Africa?. Clinical Psychological Science, 21677026231194601.

Rice, F., Riglin, L., Lomax, T., Souter, E., Potter, R., Smith, D. J., … & Thapar, A. (2019). Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. Journal of Affective Disorders, 243, 175-181.

Tay, L., Diener, E., Drasgow, F., & Vermunt, J. K. (2011). Multilevel mixed-measurement IRT analysis: An explication and application to self-reported emotions across the world. Organizational Research Methods, 14(1), 177-207.