In New Hampshire, twice as many people take their own lives than in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts and New Hampshire share more than a border, Puritan heritage, and the New England Patriots. Both states are prosperous, with median household incomes and state health care systems that rank among the top ten in the country. They’re predominantly white and largely Christian.

Despite these similarities, the two states diverge drastically in a key public health metric. In 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, New Hampshire’s gun suicide rate was four times that of Massachusetts, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New Hampshire’s overall suicide rate of 18.6 per 100,000 was more than twice as high as its neighbor.

Public health researchers say there is no single reason for the widely different suicide rates, but note that Massachusetts offers robust state-run mental illness and substance abuse treatment services, and is more urban than New Hampshire, which means that medical help for most residents is never too far away. Statewide, Massachusetts has a mental health provider for every 200 residents, whereas New Hampshire has 390 residents per provider, according to data compiled by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

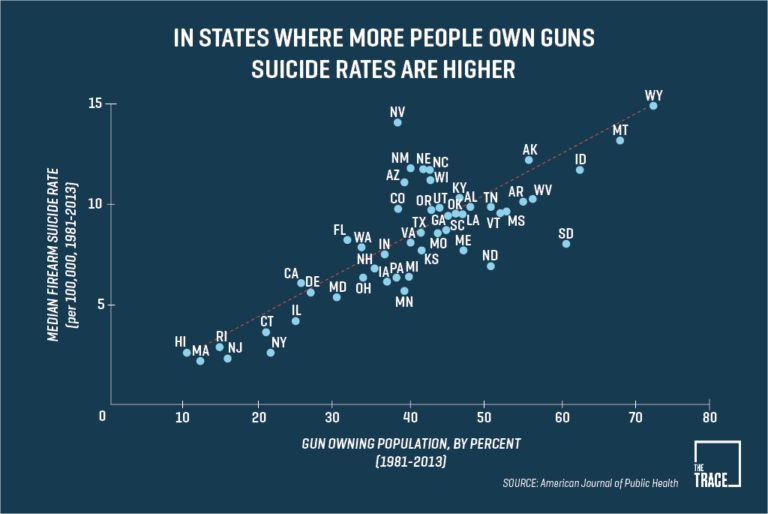

But the clearest explanation for the suicide gap, researchers say, is a 20-point difference in firearm ownership rates. In Massachusetts, an average of 13.9 percent of residents own a gun, according to a study by researchers at Boston University, and published in the American Journal of Public Health in July. In New Hampshire, an average of 35.1 percent of residents own a firearm.

The study found that for every 10 percentage point increase in a state’s gun ownership rate, there was an associated increase of 3.3 deaths per 100,000 among firearm-owning men, and a 0.5 death increase among women.

The means matters, researchers say. Most suicide attempts are not planned out in advance. People often use what they deem as the most convenient available method. If they have easy access to a gun, the odds that they shoot themselves increase dramatically.

“Suicidal ideation is not a constant state of being,” Cassandra Crifasi, a professor in the Department of Health Policy at Johns Hopkins University, tells The Trace. “You may have lost your job, or you’re having a problem with your relationship, or trouble with the law, and you’re triggered into this crisis moment and you have an impulsive thought, I’m going to use a firearm to kill myself. If you can’t get a firearm during that time, by the time you actually get your gun, you may not be feeling suicidal.”

Guns are a devastatingly effective means of ending one’s own life. Firearms suicide accounted for 6 percent of attempts and 54 percent of fatalities in one study that examined hospital data from eight states. For comparison, drug or poison overdosing accounted for 71 percent of attempts but only 12 percent of fatalities.

More than 8 out of every 10 people who used a gun to end their own life were successful.

“It’s not because gun owners are more likely to be depressed or more likely to be suicidal,” says Elaine Frank, program director for the New Hampshire-based suicide prevention organization called Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM). “It’s that an attempt with a firearm is far more likely to be fatal than an attempt with almost any other method.”

In the U.S. as a whole, half of all suicides are carried out with a gun. In Massachusetts, guns are used in just 22 percent of suicides. (The most common means in the state is hanging.)

Massachusetts and New Hampshire have very different rules about who can get guns, and how quickly. Massachusetts is one of six states where people are required to get a license before acquiring any kind of firearm, contingent on passing a background check. New Hampshire does not have this requirement.

A study of Connecticut’s licensing requirement found it was associated with a 15 percent decrease in suicide rates during the first 10 years of its enactment. In the five years after Missouri repealed its licensing laws, the gun suicide rate increased 16 percent.

Licensing laws were intended to prevent criminals from getting guns, Cristafi says. However, many of the characteristics that put someone at risk to commit interpersonal violence — such as having a substance disorder, or having a mental illness, for example — are also risk factors for self harm. Another unintended benefit is that they slow down the gun-buying process, which can protect people during a stressful time, Crifasi says. In Massachusetts, for example, acquiring a license typically takes two to six weeks.

Massachusetts is also one of just four states that requires that all firearms be stored with locks in place. Restricting access can help prevent teen suicide: A 2010 study by a team of Harvard researchers found that at least 82 percent of adolescent suicides were carried out with a gun owned by someone in the home. Another study by Michael Anestis, who runs the Suicide and Emotion Dysregulation Lab at the University of Southern Mississippi, concluded that the four states that require gun locks have firearm suicide rates that are about 40 percent lower per capita compared to states without those requirements.

New Hampshire has no laws governing gun locks or safe storage.

Some experts caution that enhanced gun laws won’t stop people from killing themselves. “We’re not going to legislate our way out of suicide,” Anestis says, adding that there’s still a lot to learn about which laws are most effective. Still, he says, laws can work in tandem with non-legislative approaches that reduce access to lethal means.

Frank, in New Hampshire, says she is enlisting gun shops to help with public outreach, in the hope of preventing suicides. In 2011, she helped launch the Gun Shop Project, which asks owners to distribute materials about suicide prevention to their customers.

“For years, the suicide prevention community didn’t want to talk about guns for fear of the politics therein and the firearm community didn’t want to talk about suicide for exactly the same reason,” she says. “We’re finally saying, the way to address this issue is for both of us to talk together collaboratively and respectfully to work together.”

She adds: “Wherever you are on the gun issue, pretty much everybody is anti-suicide.”

2 Comments

balirealestatepropertylandsalerentalbuylease.com

January 28, 2023 at 1:22 pm -The entire team was very welcoming and professional. Highly recommend to anyone

who wish to invest in Bali without doubt.

John Riley

February 1, 2023 at 4:03 pm -Thank you!