What type of Mental Illness is this and is there a solution?

Collected and published by John Riley and brought to you by Nippon.com & frontiersin.org

Hikikomori has been defined by a Japanese expert group as having the following characteristics: (1) spending most of the time at home; (2) no interest in going to school or working; (3) persistence of withdrawal for more than 6 months; (4) exclusion of schizophrenia, mental retardation, and bipolar disorder; and (5) exclusion of those who maintain personal relationships (e.g., friendships) (9, 10). Other criteria are more controversial. These include the inclusion or exclusion of psychiatric comorbidity (primary versus secondary hikikomori), duration of social withdrawal, and the presence or absence of subjective distress and functional impairment (5).

Approximately 1–2% of adolescents and young adults are hikikomori in Asian countries, such as Japan, Hong Kong, and Korea (4, 9, 11). Most cases are males (8–13) with a mean duration of social reclusion ranging from 1 to 4 years, depending on study design and setting (5, 8, 13, 14). Comorbidity with other psychiatric diagnosis is also very variable, ranging from none (13), half of cases (11), to almost all cases (12, 13). This variability may be explained by the lack of consensus on the definition of hikikomori and also because different recruitment methods were used across studies. However, there seems to be an emerging consensus that a majority of hikikomori cases have comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (5).

Hikikomori was originally described in Japan, but cases have subsequently been reported in Oman (15), Spain (13, 16, 17), Italy (18), South Korea (4, 14), Hong Kong (19), India (20), France (8, 21), and the United States (19, 22). Aside from case reports, surveys of psychiatrists from countries as diverse as Australia, Bangladesh, Iran, Taiwan, and Thailand suggest hikikomori cases are seen in all the countries examined, especially in urban areas (23).

Differentiating between hikikomori and the early stage of other psychiatric disorders can be difficult since many of the symptoms are non-specific and can be found across various conditions (21, 30). These include isolation, social deterioration, loss of drive, dysphoric mood, sleep disorders, and reduced concentration (21, 30, 31)

The government estimates that Japan has 1.15 million hikikomori, people who have withdrawn from society. But Saitō Tamaki, a leading expert on this matter, suggests that the figure is larger and may eventually rise to above 10 million. He shares his thoughts about causes of the problem and ways of dealing with these shut-ins.

On July 29, 2019, psychiatrist Saitō Tamaki gave a press briefing at the Foreign Press Center Japan on the subject of hikikomori, the phenomenon of withdrawal from society. (The Japanese term also refers to the people who exhibit the phenomenon.) Saitō, a professor at Tsukuba University, has been studying hikikomori for decades, and it was he who introduced the term and who brought the subject to wide public attention in a 1998 book.(*1)

The government has estimated Japan’s population of hikikomori aged 15–64 to be 1.15 million. But Saitō believes the authorities may be undercounting the shut-ins; he suggested that the figure could be more like 2 million. And unlike homeless people, for example, these social recluses generally live with their parents and do not have to worry about providing themselves with food or shelter. Under these circumstances, many of them can be expected to continue their secluded lives as they get older. With this in mind, Saitō believes the hikikomori population could eventually top 10 million.

Over the years many have seen social withdrawal as a cause of criminal behavior, connecting the two in cases like the Niigata kidnapping and confinement of a young girl from 1990 to 2000 and the Kawasaki mass-stabbing incident in May 2019. But Saitō rejected this view, declaring there is extremely little correlation between withdrawal and crime. “Hikikomori are defined as having spent six months or more not participating in society—without mental illness being the main cause,” he explained. In many of the cases where the media have referred to perpetrators as hikikomori, they were found to have a mental disorder and thus did not fit the definition. Saitō emphasized that the word hikikomori describes a state rather than an illness, and that the people in this state perform very little criminal activity.

Saitō sees hikikomori as decent people who happen to find themselves in a difficult situation. Japanese society has many problems, such as the lack of regular jobs, the steady rise in the average age of the population, and the trouble people have getting back into the labor force after having been forced to quit work to look after aged parents. One has to say it is not an easy society to live in.

“There’s still a lack of respect for individuals,” Saitō commented. “People who aren’t useful to society or their family are seen as having no value. When hikikomori hear the government’s rhetoric about promoting ‘the dynamic engagement of all citizens,’ they’re liable to take it to mean that their inability to be ‘dynamically engaged’ makes them worthless. This drives them into a mental corner.”

Losing Contact with Society

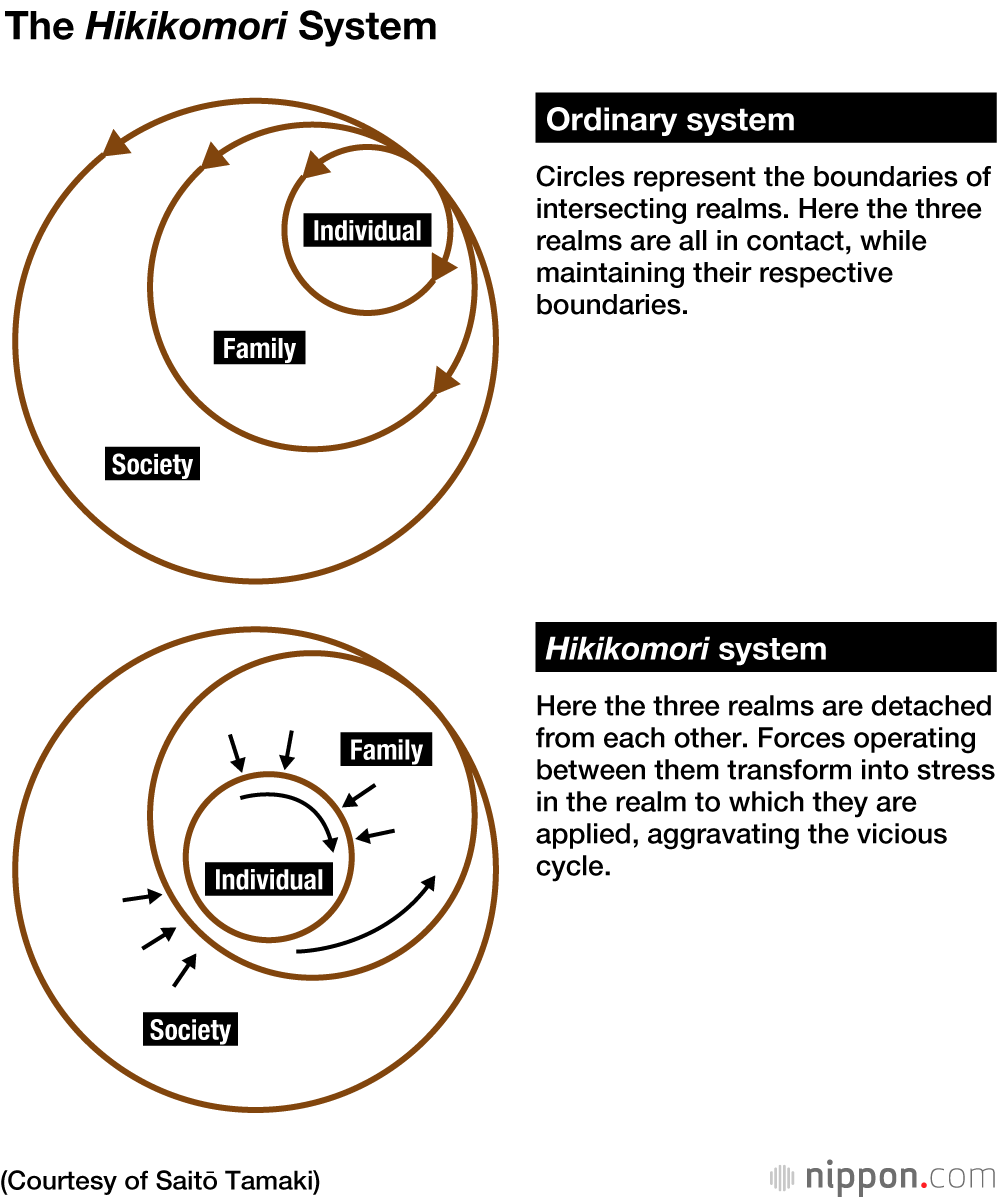

While many become hikikomori due to bullying or harassment from teachers, it is highly rare for the cause to be abuse or post-traumatic stress disorder. Once someone has entered the “hikikomori system” over the longer term, they fall into a vicious cycle, which Saitō expressed with the diagrams below. Ordinarily individuals, the family, and society are connected, but when people withdraw from society, they lose these points of contact, and their family also gradually becomes detached from society due to a sense of shame. As the situation drags on, it becomes difficult for people to return to participation in the wider world just through their own efforts. This has been described as the “80-50 problem,” whereby both elderly parents and their middle-aged children find themselves isolated.

Domestic violence becomes an issue in around 10% of hikikomori cases. Saitō explained the mechanism behind these cases: “People who have been withdrawn from society for a long time feel that their lives have no meaning or value, and they become extremely miserable. It’s too painful for them to see their situation as being their own fault, and so they begin to blame their parents for not raising them properly. They may imagine that they were abused even though they were not, and their grievances against their family can easily lead to violence.” Once this starts, he warned, it can escalate like a form of dependency.

Saitō said that it was necessary for parents to be adamant in rejecting violence by hikikomori. They must make it clear to their offspring that they will respond to such behavior either by contacting the police or by leaving the home. And if violence occurs, they must carry out their warning that very day. After leaving, they should keep their contacts to the minimum for around a week, and only return after the shut-in promises not to repeat the violence.

An International Issue

The hikikomori issue is no longer faced by Japan alone. There are estimated to be some 300,000 of these social recluses in South Korea, and a support for the families of such people has now been established in Italy. It is emerging as a problem in family-centered societies where young adults are continuing to live with their parents through their twenties and sometimes beyond.

In countries with a strong sense of individualism like the United States and Britain, where it is uncommon for grown-up children to live with their parents, the hikikomori problem is relatively small-scale, but there are many homeless young people. Since the definition of “homeless” varies from country to country, it is not possible to make direct international comparisons of the figures, but there are said to be some 1.6 million homeless young people in the United States and 250,000 in Britain. In Japan, by contrast, there are fewer than 10,000.

Social Exclusion

There is a deep-rooted belief in Japan that people with disabilities and other such difficulties should be isolated from the rest of society. Elsewhere around the world, the trend since the 1980s has been to minimize institutionalization of people with impairments. But here in Japan, to give an example, there are 300,000 beds for psychiatric patients—20% of the global total . Saitō noted, “Japan still has a culture of gathering people with disabilities under the same roof. You could say our country is peculiarly backward in this respect.”

Speaking of the Kawasaki mass-stabbing crime, Saitō said, “When these kinds of incidents happen overseas, the coverage prioritizes mourning for the victims and care for their families, but in Japan the media focuses on the character of the perpetrators and then investigates and criticizes their families. I think it’s only in Japan that the family is seen as being complicit.” This country has a history of seeing vulnerable people, such as those with mental illness or the elderly, as the responsibility of the family, and concern that the same thinking might be operating with hikikomori.

Seeking Solutions

So what should the family of a hikikomori do? Saitō introduced the case of a 21-year-old man who had been withdrawn from society for five years. After attending counseling, his parents stopped giving him pep talks or otherwise intervening at all. This led to a gradual improvement in family relations. Four months later, he finally went to see a doctor and began going to a hikikomori day-care facility, where he became friendly with other gaming fans. Two years after his first visit to the doctor, he started taking courses at a correspondence high school, and he also attended all the physical classroom sessions. His marks were good, and his condition is now stable.

Saitō offered highlights of the approach to hikikomori that he has derived from his experience: Family members are the first line of support for the affected individual, so they should consult with a psychiatrist and receive counseling. Then, he says, they should establish an external link, such as by joining a support group for families with hikikomori. Next is to slowly but steadily increase the points of contact between the family and society. While they continue to attend counseling, family members can improve their ability to engage with the recluse by consulting with regional hikikomori centers, mental health and welfare centers, or private support groups. If parents take these steps, Saitō has found that the hikikomori will start to change gradually.

Saitō also addressed the issue of aging. It is important, he noted, for parents with shut-in middle-aged offspring to draw up a lifetime financial plan for them so they can get by after the parents are gone. Parents should not fear embarrassment or be concerned about appearances as they look at the options, including disability pensions or other forms of public assistance for their children. Unfortunately, the Japanese government shows no sign of developing substantive policies or systems related to the aging of hikikomori, failing to see the urgency of the problem. So it is imperative, Saitō said, for families to make their own preparations.

Social withdrawal may start with a reluctance to go outside in reaction to a small matter. But if the condition persists for an extended period, it can lead to depression, fear of people, sleep-wake inversion, and other psychiatric conditions. So it is advisable to respond promptly by developing points of contact with society. Saitō stressed that solutions depend on hikikomori affirmatively recognizing their own condition. He concluded by noting that going back to school or getting a job should not necessarily be seen as the ultimate goal.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 30, 2019. Banner photo: Saitō Tamaki speaks at the Foreign Press Center Japan in Tokyo on July 29, 2019.)

(*1) ^ Saitō Tamaki (斎藤環), Shakaiteki hikikomori: Owaranai shishunki (社会的ひきこもり:終らない思春期 [Social Withdrawal: Puberty Without End]) (Tokyo: PHP Shinsho, 1998).

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00006/full