Douglas T. Kenrick Ph.D. and reviewed by Lybi Ma

KEY POINTS

- Evolutionary theory provides an essential perspective on the origins of our powerful motives, not a prescriptive philosophy.

- Slavish servitude to powerfully evolved motives can sometimes lead to a very unfulfilling life in the modern world.

- To make choices that lead to a meaningful life, Viktor Frankl’s self-transcendence is a better guide than misguided selfishness

Joe Horton, whose podcast encourages men to be better fathers, is a big fan of Viktor Frankl’s classic, Man’s Search for Meaning. He had seen my recent book, co-authored with Dave Lundberg-Kenrick, as well as my earlier book Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life.

Our recent conversation with Horton raised the question: When an evolutionary psychologist and an existentialist talk about meaning in life, do they mean the same thing?

Viktor Frankl and Self-Transcendance

As a neurologist and a psychologist, Frankl admitted the importance of biological and environmental factors in influencing our behaviors. He himself had been imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, where he was not only brutalized but also lost his bride to the gas chambers. Frankl stressed that, even in such extreme circumstances, individuals can make choices about how to act, think, and feel. Suffering through an insoluble situation could itself demonstrate heroism, and Frankl describes a dying woman choosing to spend her final hours not fearing death but admiring a budding tree outside her sickroom window, which she saw as a sign of immortal life.

Frankl tapped his concentration camp experiences to develop the idea of self-transcendence, which “denotes the fact that being human always points, and is directed, through something, or someone, other than oneself, be it a meaning to fulfill, or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself, by giving himself to cause to serve or another person to love, the more human he is…”

Evolutionary psychology and the meaning of life

In our book, my son Dave and I argue that an evolutionary perspective can inform a more fulfilling life. This has led to several variations of the question: If our ancestors were selected for replicating their genes, shouldn’t we feel most fulfilled by anything that serves to pass on our selfish genes?

No, but the confusion is perhaps understandable.

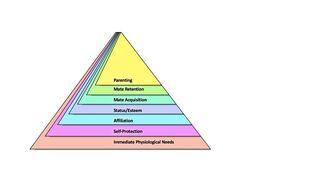

We have organized these thoughts around our renovated pyramid of needs, which is sometimes misunderstood.

Pyramid of Fundamental Motives. From Kenrick et al., 2010.

Source: Original figure, by David Lundberg-Kenrick, copyright D.T. Kenrick, used with permission

That renovation created controversy by replacing Maslow’s self-actualization with mating-related goals, and placing parenting at the top. The new pyramid, like Maslow’s, is arranged to reflect the developmental unfolding of human social needs. But many people inferred a prescriptive ideal, viewing self-actualization as something to aspire to. Hence, the new pyramid was misperceived as suggesting that having as many kids as possible is an aspirational goal.

Understanding the Past Is Not a Philosophy for Future Choices

It is critical to distinguish questions about human origins from questions about how we ought to behave in the future. In understanding our origins, we want a rigorous analysis of true causality, rather than a theory that matches our ideal preferences.

An evolutionary approach is essential to understand why many of our strong preferences are problematic in the modern world. But in deciding which choices would be best in the current world, it is a serious mistake to presume we must mindlessly enact the inclinations inherited from our ancestors. There are two reasons for this: First, acting in ways that worked for Genghis Khan a thousand years ago may not work in the modern era (most would-be Genghis Khans end up in prison or the morgue today). Second, we can choose to act in ways that do not enhance our odds of having a maximum number of offspring, or that do not enhance only our own kin group’s survival without regard to the costs on other people.

In our work, we rely heavily on research from evolutionary biology, anthropology, and evolutionary psychology to understand why people in the modern world share powerful fundamental motives with people living in traditional societies—to survive, to protect ourselves from predatory humans, to make and keep friends, to win status and respect, to attract mates, to retain mates, and to care for our families. We also address ways in which those motives can be hampered by modern technology, and how they can sometimes be out of touch with the modern world. With regard to the question of how to work around those powerful motives to live fulfilling lives in the modern world, however, we rely on research from several perspectives, and tap research findings on learning, development, and positive psychology.

Linking back to Viktor Frankl’s arguments, research by my team indicates that eudaimonic well-being, or a sense of meaning in life, links less to personal success than to caring for family members or close friends (Krems, Kenrick, & Neel, 2017).

Osceola McCarty versus Genghis Khan

Based on diverse research findings on psychological well-being in the modern world, we suggest people today emulate not Genghis Khan, but Osceola McCarty. Osceola was an African American woman, born in Mississippi in 1908. She dropped out of school in the sixth grade to help an ailing aunt, then worked as a laundrywoman until age 86 when arthritis forced her to retire. Although Osceola’s income was meager, she had no expensive possessions and saved most of her money. At age 80 she had a bank account of over $280,000 (that’s $634,000 corrected for inflation). When her banker suggested she invest all that money, she said she instead wanted to give it to other people. And she went on to donate most of her savings to help poor black students go to college. When President Bill Clinton presented Osceola with the Presidential Citizen’s Medal, she told the press:

People tell me now that I am a hero . . . I am nobody special. I am a plain, common person . . . no better than anybody else . . . I don’t want to be put up on a pedestal; I want to stay right here on the ground.

Osceola did not dedicate herself to replicating her genes, in fact, she had no children of her own. But she lived a rich life and contributed not only to her family but also to her community, thus becoming not only a hero, but also a model of self-transcendence.

References

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s Search For Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press.

Kenrick, D.T., & Lundberg-Kenrick, D.E. (2022). Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain: Human evolution and the 7 Fundamental Motives. Washington: APA Books

Kenrick, D.T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S.L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs: Contemporary extensions built upon ancient foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 292–314.

Kenrick, D.T. (2011). Sex, murder, and the meaning of life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature. New York: Basic Books

Krems, J. A., Kenrick, D. T., & Neel, R. (2017). Individual Perceptions of Self-Actualization: What Functional Motives Are Linked to Fulfilling One’s Full Potential? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(9), 1337-1352.