Brittney Chesworth Ph.D., LCSW

With health anxiety, we tend to overestimate the likelihood of severe disease. Learning how to challenge thinking errors is critical to see the probability of a threat more accurately. Examining the evidence is a cognitive behavioral therapy technique to help reframe thoughts.

It is well-known among health anxiety researchers and clinicians that people with health anxiety tend to overestimate the probability or likelihood of getting a serious disease. This threat bias, as it is often called, can make one miserable because the threat of serious disease seems to be everywhere. This leads them to interpret bodily sensations and symptoms as threatening when they are often not. Many bodily sensations and symptoms are due to other causes besides serious disease:

- body noise or normal, regulatory physiological processes that maintain the body’s homeostasis

- the anxiety or stress response

- benign and non-serious medical conditions

However, to the health-anxious person, every bodily sensation or symptom is seen as a potential catastrophe, and the cycle proceeds like this:

- They experience a symptom

- Overestimate the threat of this symptom (rather than assume the more likely causes of body noise, anxiety, or benign issues)

- They experience significant distress

- They consult with loved ones, go to the doctor, and Google symptoms

This continuous cycle takes them (and their loved ones) on an emotional roller coaster every week, making life quite challenging.

How do we learn to see threats more accurately?

One of the goals of treating health anxiety with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is to see the threat of serious disease more accurately. When one learns to stop inflating the statistics (that is, the likelihood of getting a serious disease), one will not be as threatened by every bodily sensation or symptom. Here is a technique that can help you reshape how you see this threat, called examine the evidence.

The examine the evidence activity

Examining the evidence is a great exercise for analyzing automatic thoughts that may be distorted. Recall that we tend to assume all of our thoughts are valid when many are not. We move through our day just accepting our thoughts as facts and, thus, react to them as though they are facts.

For example, you notice a funny taste in your mouth and you recall a Facebook post about a family member who was diagnosed with a brain tumor after experiencing strange tastes and smells. You conclude that you have brain cancer and begin to experience the sadness and anger that accompanies this new reality. The problem is that a lot of unnecessary suffering is taking place. If you do not learn to examine the validity of your thoughts, you will spend a lot of time and energy reacting to fiction.

An example from my own life

I smoked on and off from the age of 21 to 26. My smoking escapades would haunt me for many years after I quit. For about a decade, I was vigilantly on the lookout for any signs of lung disease. Once, I was walking up the staircase in my house and I had to catch my breath at the top of the stairs. Huh, that is weird, I thought. Why would I be out of breath from—uh oh. It hit me. This is it. Lung cancer. My time has come.

I unwisely pulled my phone out and began the Google search: shortness of breath and lung cancer. I am instantly flooded with information from the American Cancer Society to every university website that ever existed, all talking about shortness of breath being one of the key symptoms of lung cancer. Engaging in this safety behavior, of course, only further inflated my estimation of this health threat.

Fortunately, having been in therapy for health anxiety, I had a few helpful techniques to pull out of my CBT toolbox. First, I was able to recognize my thinking errors in this case, which were jumping to conclusions and catastrophizing. Next, I completed examining the evidence to help me reassess the likelihood that I had lung cancer.

Examining the evidence for the thought: I have lung cancer

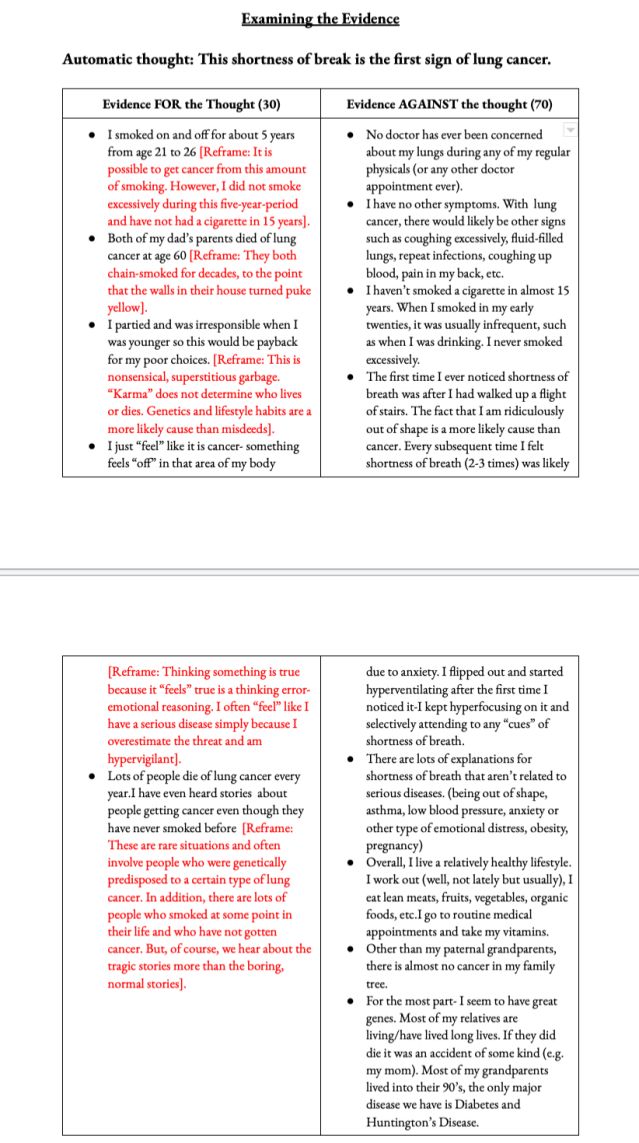

The technique is simple. You divide the page into two columns:

- Divide the page into two columns (evidence for the thought and evidence against the thought)

- After you list out all of the evidence, reframe or challenge the evidence for the thought, as some of these points might be based on faulty or biased assumptions (given that the anxious brain tends to overestimate threat and underestimate coping)

- When completed, take a look at everything. Ask yourself, if you had 100 amazing argument points to divide between the two columns, how would you divide them? Is it 50/50, 80/20, or 60/40? Which side is the big winner?

In the table, you will see a detailed example of how I completed this activity to address my anxious thoughts about having lung cancer.

Don’t be shy about writing down every piece of evidence in the evidence-for section, even when you know it is unrealistic or even silly. You need to acknowledge all the reasons you feel convinced that this thought is true. By acknowledging it, you bring the discussion out into the open and allow yourself to challenge any distorted thoughts. If you pretend they aren’t there, you miss out on the opportunity to reframe them. They will, most definitely, return at some point later, such as when you are in another vulnerable anxious state.

In conclusion

This exercise helped me to see the alleged threat a bit more realistically. Yes, it is possible that my shortness of breath was, indeed, the first symptom of lung cancer. It is also possible that tonight I slip, hit my head, and drown in the bath, or that tomorrow I get shot while shopping in the toy aisle at Target. Many threats are possible but how many of them are probable?

And seeing all of the evidence for and against my having lung cancer allows me to better grasp this low probability. In CBT sessions with my clients, we regularly whip out Google documents to examine the evidence of their anxious thoughts about their health. On almost every occasion, we find that the evidence-against column looks robust and meaty, while the evidence-for column looks empty and hollow.

Anxiety leads us to inflate the numbers. Use this exercise to help you see the probability of serious disease more accurately.